Article Tangible To In-Tangible

|

Isobel Johnstsone, June 2015

Curator, Arts Council Collection 1979-2004 |

Nahem Shoa

Nahem Shoa

Nahem Shoa's small oil painting Desmond of 1997 is a recent arrival in Exeter Museum and Art Gallery. It hangs beside what is probably the most remarkable portrait in RAMM's collection. Thought once to be of Olaudah Equiano and now of Ignatius Sancho, Portrait of an African, may be by the 18th century Scottish painter Alan Ramsey. Portraits of black subjects are rare in galleries even today and Shoa's picture makes a strong point by its very existence here. Artistically it measures up. It also reveals Shoa's painting skills – strong structure that is the legacy of Cézanne and Cubism, and vibrant colour created from a palette devoid of black and earth pigments. The close-up pose reflects the popular intimacy of today's media. This contemporary portrait of fellow painter Desmond Haughton is a small measure of what Shoa has been best known for to date.

From his earliest student years in Manchester he set out to be a painter and after graduating in 1991 won many prizes for his portraits. At that time painting was just one of several ways of expressing oneself as a visual artist. Indeed it was regarded by some as a medium that had had its day and many artists were making conceptual work using text, as well as using photography, video and installation. Nonetheless from the mid 1970s vigorous re-interpretations of painting had emerged 'The New Spirit in Painting' at the Royal Academy in 1981 had shown 30 painters – all male - from Europe and the U.S.A. including Georg Baselitz, Sigmar Polke, Sandro Chia, Julian Schnabel, Francis Bacon, Howard Hodgkin and Ron Kitaj. Later in the decade the new 'Glasgow Boys', painters of a dark kind of Social Realism including Ken Currie and Peter Howson, achieved unprecedented success for Scottish art. By 1997 the Sensation exhibition at The Royal Academy brought the Y.B.A.s to the fore and London became a place of international interest, largely because of the patronage of Charles Saatchi, who supported many of the so-called Young British Artists emerging from Goldsmiths College, among them Damian Hirst, Sarah Lucas and the Chapman brothers. Apart from Jenny Saville's self-portraits there was little representational painting in this show that Shoa as a dedicated painter from life would have found of interest.

Shoa had already found a congenial mentor in the London born painter and family friend, Robert Lenkiewicz, whom he visited from 1986 to 1996 for tutorials in Plymouth. Lenkiewicz was a brilliant technician who could turn out beautifully worked portraits. Virtually self-taught (he is still un-acknowledged by the London art world) he encouraged his young pupil to paint with 'knowledge' rather than 'hope'. Post-graduate study at the Slade from 1992-94 provided further opportunity to absorb the discipline of other kinds of painting from life which were achieving recognition having being virtually ignored in the '60s. This had been identified as the 'School of London' by the former Pop artist Ron Kitaj in his introduction to an Arts Council exhibition 'The Human Clay' as far back as 1976. Kitaj wrote at a time when life study was disappearing from many art school programmes. In this so-called 'School' were Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach, who had been brought to England as young refugees from Nazi Germany before the Second World War and Leon Kossoff, who was born in London of Jewish parents who fled from Russian pogroms in 1906/7. This was an affirmation of the study of the human form as a fundamental of painting history and an essential future subject. Kitaj's used the poet W.H.Auden's statement 'To me Art's subject is the human clay' to make his point. Shoa's parents were both from Jewish backgrounds, as was Lenkiewicz, and doubtless something of their shared history will have reinforced Shoa's decision to be a painter of human life.

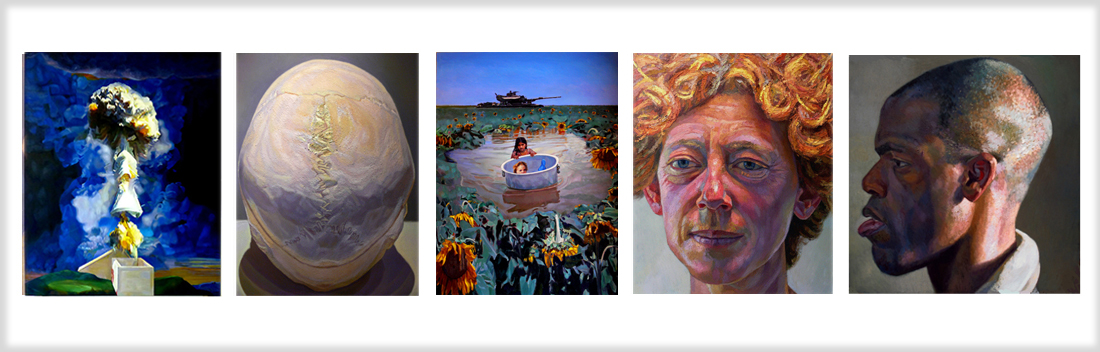

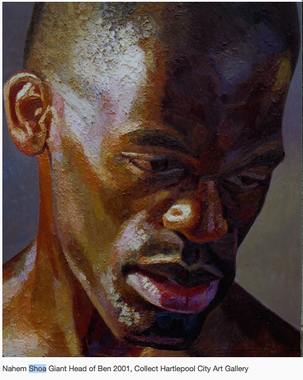

If the strength of Shoa's oil painting technique is evident in the small portrait of Desmond it is even even more so in the Giant Head, Ben, 2001, purchased in 2004 by Hartlepool City Art Gallery (with assistance from The Art Fund). Giant Head, Ben measures 180 x 150cm and is from a series of large heads shown in various exhibitions around the U.K. from 2001 to 2007. The influence of Freud can be seen in these heads in the top lighting and the way the planes of the face are scrutinised. The scale, however, is closer to an Andy Warhol screenprint. But whereas Warhol icons remain remote Shoa's close-ups insist on intimacy through their gaze and grainy reality. They took months of work while pigment could build up to an inch thick in places. This insistence on tangible materiality as a means of giving work vitality connects it to Auerbach and Kossoff – a point made in the Hartlepool City Art Gallery Uncompromising Study exhibition in 2006 where Giant Head, Ben was hung beside an encrusted Auerbach oil Shell Building Site. This show also included life sized clothed portraits, for example a particularly fine one of Caroline Poole, the curly haired subject also of one of several other giant heads. These were remarkable enough but the huge looming black presence of Giant Head, Ben is a new icon. Rubens, Delacroix and possibly Ramsey were among the few painters who made portraits of black individuals but not on this scale or with this kind of painterly insistence. Close inspection reveals how Ben's blackness is achieved through a range of spectrum colours.

Having decided to call themselves New British Realists Shoa, Desmond Haughton and a group of friends (including Gbenga Lumoka, Caroline Poole, Geoff Gannage, Christopher Potter and Myrna Shoa) added Multiculturalism to their ambitions for new ways to give traditional painting power and relevance. In 'Multi Culture/Youth Culture' at Plymouth City Art Gallery in 2004 and 'Giant Heads and Multi Culture' at Hartlepool City Art Gallery the same year, in addition to frontal close-ups and back views of heads by Shoa, there were life-size nude studies of black and white men and women, and groups of multicoloured friends in domestic interiors.

Having decided to call themselves New British Realists Shoa, Desmond Haughton and a group of friends (including Gbenga Lumoka, Caroline Poole, Geoff Gannage, Christopher Potter and Myrna Shoa) added Multiculturalism to their ambitions for new ways to give traditional painting power and relevance. In 'Multi Culture/Youth Culture' at Plymouth City Art Gallery in 2004 and 'Giant Heads and Multi Culture' at Hartlepool City Art Gallery the same year, in addition to frontal close-ups and back views of heads by Shoa, there were life-size nude studies of black and white men and women, and groups of multicoloured friends in domestic interiors.

Shoa was the leading force in the group and well equipped to set himself up as a painter of contemporary multicultural life, having a Scottish Russian mother and a father from the Yemen ( of Ethiopian descent). Notting Hill where he lived in London was racially mixed. Shoa's ambition was to make sure his multiculturalism was not the art of outsiders. It had taken time for ethnicity to find expression in the the U.K. 'The - all male - New Spirit in Painting', which opened in the same year as the Brixton riots, did not represent a single 'ethnic' artist. Among government attempts to alleviate tensions The Arts Council's Glory of the Garden policy of 1984 spread more funding beyond London and supported new initiatives for ethnic (as they were then called) minorities. For visual artists this meant separate exhibitions. 'Into the Open', the first national exhibition of black artists in Britain was held at the Mappin Art Gallery in Sheffield in 1984.

Two years later an attempt at 'an innovating synthesis... of...cultural plurality' - 'From Two Worlds' - was held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London. 'The Other Story' at the Hayward Gallery in 1989 was an exhibition of Afro-Asian Artists in post-war Britain. By the early 1990s when Shoa and his friends set out on their multicultural mission black artists were in evidence using various media. Not surprisingly perhaps, in view of the macho character of so much painting in the 1970s and '80s, women who had something to say, like Mona Hatoum and Sonia Boyce, avoided paint. If, like Rasheed Araeen and Keith Piper, they did paint the medium was used in a deliberately unsophisticated way and they used confrontational iconography. Shoa was determined to keep painting and work within a tradition so well executed it could not be ignored. He constantly studied the work of past masters and welcomed comparison with living artists. In Uncompromising Study, the show he curated for Hartlepool Art Gallery in 2006 which went on to the Herbert in Coventry, his work was hung beside that of Freud and Auerbach, as well as his friend Lenkiewicz.

Two years later an attempt at 'an innovating synthesis... of...cultural plurality' - 'From Two Worlds' - was held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London. 'The Other Story' at the Hayward Gallery in 1989 was an exhibition of Afro-Asian Artists in post-war Britain. By the early 1990s when Shoa and his friends set out on their multicultural mission black artists were in evidence using various media. Not surprisingly perhaps, in view of the macho character of so much painting in the 1970s and '80s, women who had something to say, like Mona Hatoum and Sonia Boyce, avoided paint. If, like Rasheed Araeen and Keith Piper, they did paint the medium was used in a deliberately unsophisticated way and they used confrontational iconography. Shoa was determined to keep painting and work within a tradition so well executed it could not be ignored. He constantly studied the work of past masters and welcomed comparison with living artists. In Uncompromising Study, the show he curated for Hartlepool Art Gallery in 2006 which went on to the Herbert in Coventry, his work was hung beside that of Freud and Auerbach, as well as his friend Lenkiewicz.

Ziggy

Ziggy

Shoa is politically aware, not least of the chauvinist label attaching to male artists using female models. In conversation he makes it clear how his models are his friends or become friends. They have to pose over many weeks. He is respectful in the poses chosen, often letting the models decide On occasion he would set something up which echoes a famous picture, for example the black reclining figure suggested by Velazquez Rokeby Venus or black male back by Ingres's Valpinçon Baigneuse. Sometimes the connection with old masters is not particularly obvious. The 2001 painting Kiki and Helen (48” x 35”) is of a lesbian couple one naked the other clothed. The frontal posture of the naked figure echoes Henri Matisse, even Stanley Spencer, but for Shoa a more appropriate comparison would be with Rembrandt's Jewish Bride because of the way in which the hands touch. At this time as we have seen women artists tended to avoid painting as a means of articulating feminist ideas. Jenny Saville was one of the few to make a feminist point by painting oversize nude self portraits - but she achieved these using photographs. Kiki and Helen is an assuring rather than attention-seeking statement for feminism, achieved entirely by working directly from life.

Following the huge effort involved in the many exhibitions up to 2007 Shoa continued painting large and luminous studies of skulls which he had begun in 2006. From whole skulls he moved on to enlarge details of eye and nose sockets trying to lose the 'vanitas' association in a play of rapturous colour. As the series was drawing to a close Damian Hirst exhibited his first skull and this closed the door on the theme for Shoa. He turned to other subjects – hugely various paintings bursting with incident, including floods and nuclear explosions which continue with the theme of death. These inevitably drew on 'unreal' sources, photographs, TV and film as well as memory. This large body of work has not yet been shown. Its research seems to have sparked a mood of introspection and some cynicism about human progress. Most recently Shoa made another dramatic move – from a tangible kind of reality to something quite intangible – where, contrary to all previous methods of working, accident was allowed to prompt imagination.

The transition was marked in 2014 by a series quizzically called The Evolution of Man? These are one metre-wide Rotary pen drawings in black ink on brilliant white conservation paper in which he gives license to a long-held fascination with primates. Monkeys with huge penises cavort ecstatically. Some, rather worryingly, lie across the lap of a Madonna figure - an idea suggested by a painting like Matthias Grunewald altarpiece of Saint Dorothy and Virgin and Child. The concise Germanic line gives these drawings Gothic intensity. Sources also include 19th Century Japanese Shunga prints and Aubrey Beardsley's illustrations to Aristophanes's Lysistrata. In spite of the sacrilegious and pornographic iconography the mood of these animals, which have penises larger than their brains, is playful. In Shoa's words they: 'proudly act out themes that are played out by humanity, everyday in human species all over the world'. He seems to have a poor view of man who, in one respect at least, has got stuck at the monkey stage.

Teenage Grotto

Teenage Grotto

As a counterpart to the precise delineation of The Evolution of Man?, Shoa began to make small acrylic paintings in which colour and a much more fluid medium suggest less tangible realities. Men, women, children and (inevitably) monkeys inhabit territory that is somewhere between a futuristic film set and paintings by Odilon Redon and Edvard Munch, and with Klu Klux Klan figures after Philip Guston. The colour is rich and luminous, like stained glass. There are elements of threat. Titles such as Teenage Grotto, Drug Dealers, Looter and Superman suggest that we are still exploring a contemporary Zeitgeist not unconnected with the earlier oils. There is new poetry, however, and potential for a different kind of inventiveness. These are an important step towards much larger pictures.

By loosening his previously tenacious grip on the visible world Shoa unlocked potential for a different, more personal language. He altered the way he manipulated paint, colour and texture. The artists Chris Ofili, Peter Doig, Gerhard Richter, Neo Rauch and Adrian Ghenie were important sources for these new ways forward. Subject matter did not need to be too precise or relate to actual experience. Doig, who had a surprisingly varied way of applying paint, had shown that quite banal subjects might be a threshold to visual adventure. Thus the power of paint itself, its viscosity, colour and texture, now engaged Shoa in expansive new paintings where he floated colour washes on to pristine canvases, letting it coalesce and drip in order to see what forms suggested themselves. He then worked parts up in detail, leaving other parts less defined.

By loosening his previously tenacious grip on the visible world Shoa unlocked potential for a different, more personal language. He altered the way he manipulated paint, colour and texture. The artists Chris Ofili, Peter Doig, Gerhard Richter, Neo Rauch and Adrian Ghenie were important sources for these new ways forward. Subject matter did not need to be too precise or relate to actual experience. Doig, who had a surprisingly varied way of applying paint, had shown that quite banal subjects might be a threshold to visual adventure. Thus the power of paint itself, its viscosity, colour and texture, now engaged Shoa in expansive new paintings where he floated colour washes on to pristine canvases, letting it coalesce and drip in order to see what forms suggested themselves. He then worked parts up in detail, leaving other parts less defined.

Suspended Social Order, 2014, 70 x 240cm, is from from the first series of new paintings and like them all was conceived in two halves. It is probably an autobiographical journey of some kind as well as a celebration of the grotesque in contemporary society. On the right is a half-waking boy reclining in what looks like an early Italian landscape except that it is red with a bright blue lake. There is a homage to Goya in the giant appearing top right. A drama of sorts is enacted on the centre fold - where a simean man prevents a girl from heading left and a man with a monkey on his shoulders engages with a woman in yellow. More monkeys appear appear in the left foreground and above is another landscape in an even more deliquescent state, with a network of ultramarine paint spots. Beyond a distant hill is a moustachioed sleeping profile, who may represent the artist.

In Dreams of Making a Better Life from a 70 x 240cm series in progress this year. The canvas surface has been treated with acrylic gel and resist paint that allow subsequent layers to adhere in various ways, thin films of colour and blobs and drops. We are transported out of a barely tangible world into an intangible dreamlike place where primates are entirely in control. A red monkey with a mane-like helmet holds commands the centre-fold arms outstretched. More red monkeys form a pyramid behind that opens out like a Rorschach blot. On the right again is a red landscape with a blue lake. A green hilly foreground encloses a space-helmeted head. Opposite is a bearded man in a flying jacket, an energetic Bauhaus blond and other figures which float amid a sea of boulders.

This is a futuristic paradise more brilliant and elusive than the primitive world depicted by Paul Gauguin, Pierre Bonnard and The Nabis when they intensified colour and pattern for emotional effect. Shoa's new visions are informed by more sophisticated memories than the innocent primitive world which the Symbolists sought over a century ago. His subconscious is packed with the complex and catastrophic history of the 20th century. If he is to capture something of a 21st century Zeitgeist he is learning that he must set his material free – stretch and if necessary overturn previous painting tenets, so that this august medium can compete with the energy and luminosity of film and TV.

Isobel Johnstsone, June 2015

Curator, Arts Council Collection 1979-2004

SEE Nahem Shoa's New Imaginative Work

This is a futuristic paradise more brilliant and elusive than the primitive world depicted by Paul Gauguin, Pierre Bonnard and The Nabis when they intensified colour and pattern for emotional effect. Shoa's new visions are informed by more sophisticated memories than the innocent primitive world which the Symbolists sought over a century ago. His subconscious is packed with the complex and catastrophic history of the 20th century. If he is to capture something of a 21st century Zeitgeist he is learning that he must set his material free – stretch and if necessary overturn previous painting tenets, so that this august medium can compete with the energy and luminosity of film and TV.

Isobel Johnstsone, June 2015

Curator, Arts Council Collection 1979-2004

SEE Nahem Shoa's New Imaginative Work